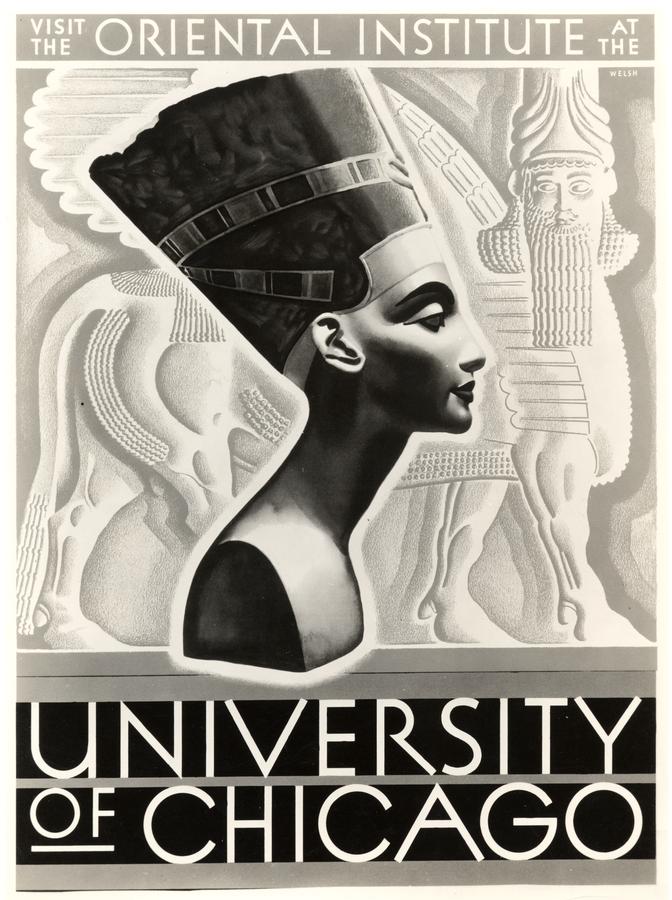

Video of The Danh Vo exhibit on display at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Review of David Schloen’s The House of the Father as Fact and Symbol: Patrimonialism in Ugarit and the Ancient Near East (2001)

The weirdly conservative world of J. David Schloen

In Roland Boer's Blog

Read the rest.

In Roland Boer's Blog

As part of my sacred economy project, I have finally finished working through J. David Schloen’s The House of the Father as Fact and Symbol: Patrimonialism in Ugarit and the Ancient Near East (2001). It is eminently useful, obsessive, rambling, conservative, and ultimately flawed. The basic thesis is that Max Weber’s patrimonialism (patronage) is a valid category for understanding the politics and economies of pretty much every society in the ancient Near East, at least until the ‘Axial Age’ in the first millennium when ‘rationalisation’ began. He also deploys Paul Ricoeur for his theoretical armoury in order to provide what he feels is a ‘dialectic’ between fact and symbol (it is really more of a wooden correlation)...

Read the rest.

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Oppenheim Papers at Regenstein Library

Announced today by The University of Chicago Library

Special Collections Research Center is the new Guide to the Adolf Leo and Elizabeth Oppenheim Papers 1988-1980.

Oppenheim, Adolf Leo at CDLI

A. Leo Oppenheim in Wikipedia

And of course Erica Reiner's chapter A. Leo Oppenheim in Shils, Edward. 1991. Remembering the University of Chicago: teachers, scientists, and scholars. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.To the best of my knowlege this is not available online

Descriptive Summary

Title: Oppenheim, Adolf Leo and Elizabeth. Papers Dates: 1988-1980 Size: .25 linear feet (1 box) Repository: Special Collections Research Center

University of Chicago Library

1100 East 57th Street

Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A.Abstract: This collection consists of documents relating to the lives of Leo and Elizabeth Oppenheim. A majority of the documents and correspondence relate to the couple's sustained attempts to leave Europe and immigrate to the United States during World War II. Documents within this collection date from 1888 to 1980, with the bulk of the documents dating between 1938 and 1946

An interesting autobiographical sketch by Elizabeth Oppenheim can be found here. From Robert Oswalts Preface:

Elizabeth Oppenheim, or Lilly as her friends called her, was invited sometime in 1978 to speak to a women's group in Berkeley on her escape from Nazi-occupied Austria and later from France. She prepared for this talk by writing out a 4,000-word account entitled, "Emigration history of A. Leo Oppenheim (1904-1974) and Elizabeth Oppenheim (nee Munk)." I had been intrigued by this chronicle and wanted to know more of the details of how she and her husband had managed to survive, and thus, at intervals in the period from about 1989 to 1990, when she was a bed-bound invalid but had not yet lost her ability to speak, we went over each item in her account, I asking questions and she answering as well as she Could -- much had been forgotten, but many new incidents were revealed. The questioning also turned to the happier days in Austria before the Anschluss and to her childhood and family background and, at the other end of her life, to the progress of the careers of herself and her husband. The account illustrates very well that in perilous situations survival often depends upon getting help from friends and other concerned persons, especially those with influence. It also depends on one's own resourcefulness, and depicted here is a remarkably resourceful woman who, as a foreigner, was not allowed to work in France at a steady job, even for minimal subsistence, and yet found a way to turn her artistic skills into a modest livelihood; and who, when living at the poverty level on first arrival in America, turned these same skills to increasing their joint income so that she and her husband could rise to a successful and comfortable life.And see:

The information gained in the interviews was taken down as a 100 or so short notes. Since Lilly's death, I have sorted them and interfiled them chronologically with the paragraphs from her own account. Her original text is reproduced in italics; the additions are in ordinary typeface and are cast in the first person and worded to blend with the original sketch. Lilly's 1978 account is the more gripping story and whoever wants only her text can read the italicized portions of what follows. In editing the additions, however, I have followed the principle that, rather than cut out some parts to make a tighter adventure story, it is preferable to retain all information, as this is the only record of much of Lilly's life.

Oppenheim, Adolf Leo at CDLI

A. Leo Oppenheim in Wikipedia

And of course Erica Reiner's chapter A. Leo Oppenheim in Shils, Edward. 1991. Remembering the University of Chicago: teachers, scientists, and scholars. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.To the best of my knowlege this is not available online

Monday, January 7, 2013

Praise for the OI's Open Access Policy

Adam McCollum of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML), Saint John’s University writes in hmmlorientalia:

Two important Syriac books from OI (Chicago)

Two important Syriac books from OI (Chicago)

For some time the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago has very generously made available PDFs of its great store of books in Egyptology, Assyriology, archaeology, history, etc. Very recently the accessibility of two books of definite interest for Syriac scholars have been announced:

This is part I, but that is all that appeared. The only complete edition is that from the Bar-Hebraeus Verlag, 2003. Full information on manuscripts, editions, and studies will be found in Hidemi Takahashi’s always handy Barhebraeus: A Bio-Bibliography (Piscataway, 2005), 147-173.

- Martin Sprengling and William Creighton Graham, Barhebraeus’ Scholia on the Old Testament, pt. I, Genesis-II Samuel, Oriental Institute Publications 13 (Chicago, 1931).

Lagarde, with his interest in the Greek versions of the Hebrew Bible had worked on this Syriac text before and published it (as he did for other works) in Hebrew script (see here for bibliography of Epiphanios in Syriac). I cannot refrain from quoting Sprengling’s humorous report (p. ix) on Lagarde:

- James Edward Dean, Epiphanius’ Treatise on Weights and Measures: The Syriac Version, foreword by Martin Sprengling, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 11 (Chicago, 1935).

…our last predecessor in a similar undertaking [work on the Syriac Bible], the curious Paul de Lagarde of Göttingen. Lagarde had therefore undertaken an extensive study and a series of editions of this Epiphanius material. In his usual fashion he scattered this work around in a series of odd publications, many of them in small editions. These are not easy to get and, when obtained, generally not easy to use. The Syriac text, for example, he printed in Hebrew letters, because there was no Syriac type in Göttingen. His translation into German is curious. In various notes voicing his disgust and alleging (a thing Lagarde does not often admit) his incompetence, he shows that this was to him no labor of love. Jülicher’s statement in Pauly-Wissowa that the text is “sehr schlect ediert” by Lagarde is, indeed, too harsh a judgement. But a better, more easily accessible, more usable, and in every way more definitive edition than that of Lagarde, dated 1880, was clearly called for.Hence the book by Dean, now eminently accessible after not being so for many years.

The Greek fragments of Epiphanios’ work (CPG 3746, cf. 3747) are not all that remains in addition to the Syriac: Georgian (CSCO 460-461, by M. van Esbroeck) and Armenian (CSCO 583, by M. Stone and R. Ervine) witnesses have also been published since the time of Dean’s Syriac text. In this work, interesting in and of itself, we have another opportunity for cross-linguistic comparison.

So, hats off to the OI for sharing its resources!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Stumble It!

Stumble It!