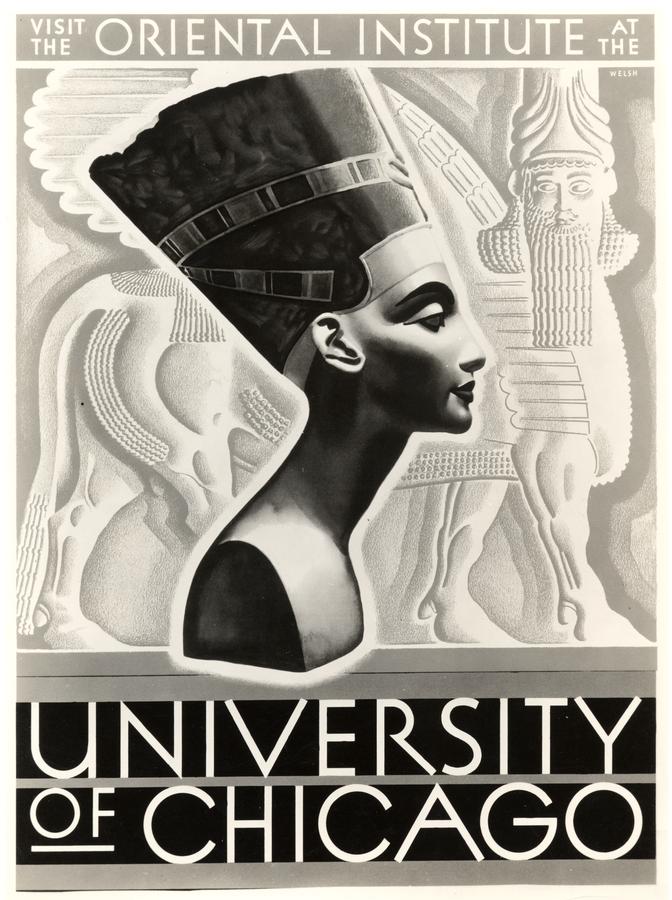

Keepers of University collections reveal the pieces closest to their hearts.

...

Jack Green, Chief Curator, Oriental Institute

Situated along the bustling trade route between Egypt and Syria, the ancient city of Megiddo (in modern-day Israel) was a crossroads of globalization in the late Bronze Age. A massive archaeological excavation here by the Oriental Institute in the 1920s and ’30s unearthed 382 pieces of carved ivory in a palace cellar. Combs, ointment containers, and decorative trinkets bearing aesthetic influences from surrounding regions were stacked in a single room.

“We actually don’t know why all these pieces were found together,” though people have been known for several centuries to hoard and collect ivory, says Green. Even more mysterious, the treasure pile was topped with the remains of a dead cow, perhaps as part of a sacrifice or ritual. The OI holds the only collection of Megiddo ivories in North America. “They’re wonderful because they really show the trade connections in the eastern Mediterranean at that time.”

Female Sphinx Plaque, ivory, Megiddo, Stratum VIIA, Late Bronze IIB (1300–1200 bc). A22213.

This well-preserved ivory sphinx speaks to Megiddo as a cultural crossroads infused with the influence of globalization. Though situated far from Egypt, locals created artistic objects that captured their perceptions of the distant land. “They’re taking an Egyptian motif—the sphinx—and combining it with other motifs that might be thought to be Egyptian to create this hybrid,” Green says. “But it’s really not something that you’d normally see in ancient Egypt.” Resident Egyptologist Emily Teeter adds, “an Egyptian would look at this and think, ‘It’s supposed to be Egyptian? You’ve got to be kidding me.’”

Gaming Board, ivory and gold, Megiddo, Stratum VIIA, Late Bronze IIB (1300–1200 bc). A22254 A&B.

“If I had to choose one object amongst all of them, this gaming board would probably be it,” says Green. Designed for a Parcheesi-like pastime of the upper crust known as the “game of 58 holes,” this “super luxe” item was a sign of worldly sophistication. Made of fragile elephant ivory, the piece retains much of its gold embellishment and is one of few such boards ever discovered intact. “You could imagine a governor or wealthy Canaanite mayor using one of these,” Green says. “An international-style gaming board was very much the fashionable thing.”

Emily Teeter, Egyptologist and Research Associate, Oriental Institute

Annuity Contract, papyrus, ink (detail), 365–364 BC, Late Period, Dynasty 30, Reign of Nectanebo, 22 December 365 BC–20 January 364 BC, Faiyum, Hawara, purchased in Cairo, 1932. OIM 17481.

“I love the resonance of ancient and modern in this piece,” Teeter says, describing an expansive papyrus scroll that details a northern Egyptian marriage contract from 364–365 BC. Written in Demotic script, a later form of hieroglyphics, the document specifies that the man must provide his wife a set amount of silver and grain each year—for life. “He has to continue to pay this, regardless of what house she’s living in,” says Teeter, explaining that divorce, much like now, was quite common in ancient Egypt. “There was no real stigma to it.” Penned on multiple sheets of costly papyri affixed together, each of which features only a small amount of text, the contract itself was a status symbol for the couple. “They didn’t need this much papyrus,” says Teeter. “They’re showing off.”

A Complaint from Tomb Builders, limestone, pigment, New Kingdom, Dynasty 20, Reign of Ramesses III, ca. 1182–1151 BC, Luxor, Deir el-Medina, purchased in Luxor, 1936. OIM 16991.

This limestone plaque inscribed with cursive hieroglyphics chronicles the first recorded labor strike in Egyptian history, circa 1153 BC. “It’s such a humble-looking object, but it says so much about the society,” Teeter says. After being shorted on pay, builders constructing tombs for Ramesses III’s sons in the Valley of the Queens walked off the work site and put down their tools at a local temple.

“We are exceedingly impoverished,” they wrote to the vizier overseeing the project. Though the plaque itself breaks off midtext, the result—the tombs were finished—attests to a successful strike. “People think of ancient societies where the pharaoh is all powerful,” Teeter says, “but there was a lot of give-and-take.”

Stumble It!

Stumble It!