This unsigned tribute to George Hughes appeared on pp. xv-xviii of

SAOC 39. Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes, January 12, 1977. J. H. Johnson and E. F. Wente, eds. 1976.

GEORGE R. HUGHES

George R. Hughes was born a farm boy near Wymore, Nebraska, January 12, 1907, the elder child of Evan and Pyne Hughes. His was a Welsh community; until he went to school, he spoke only Welsh, and he has remained proud of his Welsh heritage all his life. He began his schooling in the proverbial one-room schoolhouse, one year later than most, since his parents wanted him to wait until his younger sister would also be old enough to go, so they could walk back and forth together. When the time came to transfer to high school, the nearest high school would not accept his credentials, and he had to take an entrance exam. Although he passed easily, he was almost denied admission because the school system lost his exam paper. Just before he was to take a repeat exam, the original was found, and he was on his way. He went on from high school to the University of Nebraska, where he felt lost in the crowd. But despite the new environment he excelled in his studies and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1929.

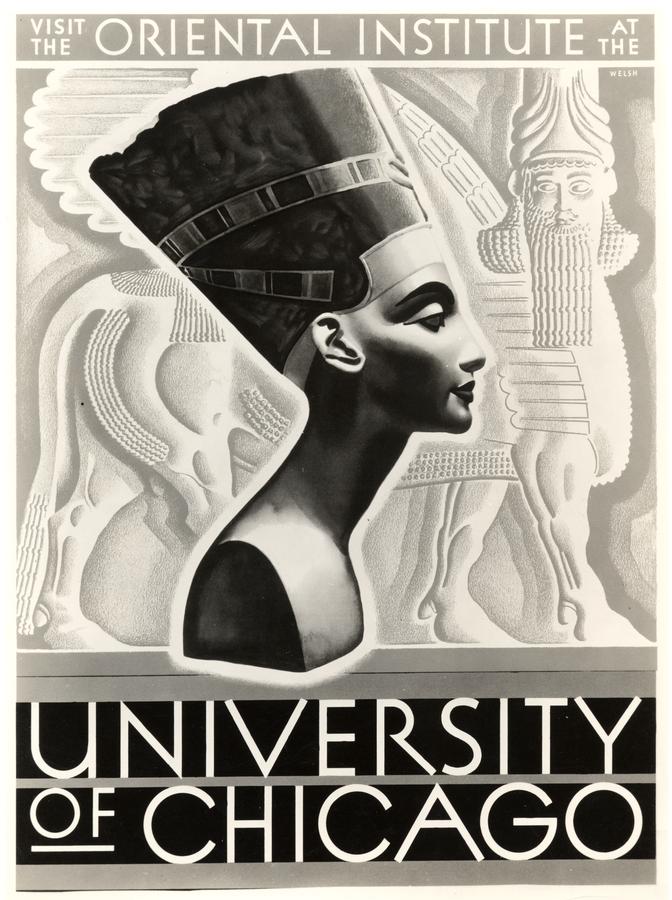

The next fall the small-town boy ventured out of Nebraska, moving to Chicago to attend McCormick Theological Seminary. He studied introductory Egyptian under O. R. Sellers and, in the summer of 1931, took a course with William F. Edgerton at the Oriental Institute. Edgerton recognized his ability and urged him to devote himself to the study of ancient Egyptian. During his last year in the seminary, when he was class president, he not only won the class prize for best preacher, but he also was awarded the Nettie F. McCormick Fellowship in Old Testament to continue his formal education. In the fall of 1932 he formally registered in the Divinity School of the University of Chicago, by which time he had become an ordained minister and had taken as wife Maurine G. Hall, who has remained his constant companion and helpmate for over forty years. Once at the University of Chicago, he studied both Hebrew and ancient Egyptian in the Department of Oriental Languages and Civilizations.

Within a couple of years of his arrival at the University of Chicago he transferred from the Divinity School to the Department, and, when it came time to choose a dissertation topic, he decided that there was more range in Egyptology and so began a dissertation on Demotic land leases under William F. Edgerton. He was already a research assistant in the Oriental Institute, working for Edgerton on Spiegelberg's materials for a Demotic dictionary at the then lavish salary of $2000 per year. For about eight years he shared a tiny, low-ceilinged, hot, stuffy office on the third floor with other young research assistants, known collectively and informally as "Breasted's Brain Trust." To this day the venetian blind that he helped purchase to keep out the hot afternoon sun hangs in his former office, providing shade for new generations of orientalists, busy at their work. But not all his time was spent in purely academic pursuits-he was also a noted member of the Oriental Institute softball team.

During World War II he went to Washington along with several of his colleagues from the Oriental Institute, including his former teacher Edgerton, and spent the years from 1942 to 1946 in Intelligence, applying his abilities in deciphering ancient Demotic to modem cryptography. Following the war, in 1946, he went to Chicago House, Luxor, as an epigrapher working first in the Temple of Khonsu and at the Bubastite Portal in Karnak. When Professor Richard A. Parker resigned his position as field director of the Epigraphic Survey, George Hughes became field director on New Year's Day, 1949, a post he was to hold through difficult years until the spring of 1964. Even the bombing of Luxor during the 1956 war could not force him to abandon his responsibilities at Chicago House.

He is by nature a thorough and painstaking person, and perhaps these traits are best exhibited in the reams of collation sheets he prepared over the years that he served as epigrapher and field director of the Epigraphic Survey. Backing the accuracy of many drawings of the expedition's past publications, as well as of some yet to appear, are the exacting, often minute corrections and additions made on the collations sheets in Hughes's neat hand. To work as a fellow epigrapher with him in temple and in tomb was a real educational experience; one learned how to interpret traces on a badly damaged wall by visualizing what the scene or text looked like originally. In this way he was a great teacher in the field as well as in the classroom.

While he was demanding as a field director, he was far from being a "Cruel Father" (the title of one of his articles). As head of Chicago House he was a kind and generous father to those who lived and worked with him. In Luxor he is still remembered not only for his devotion to the task of recording ancient monuments but also for the magnanimity and graciousness that he displayed through his interest in the personal welfare of those with whom he came in contact. His charity and his ability to sympathize with personal problems have made him a rare and very special person, both at home and abroad.

He eschews lavishness and bravado; the simple things of life give him great enjoyment. In Luxor he would sometimes accompany an ailing staff member into town on a visit to the pharmacy on Station Street. While waiting for the prescription to be filled, he seemed to derive great contentment from merely chatting and watching the people come and go. A big event during the Luxor days might be going down to the railroad station to meet someone. Once Stephen Glanville and the then young Harry Smith were visiting Chicago House. Smith, who had gone off for the day on a side trip, was returning on the night train, so Glanville and Hughes went to the station to meet him. Sitting on a bench on the platform, the two scholars talked about Demotic and related subjects. Smith's train arrived and discharged him into the customary bedlam of shouting, running, and pushing. He saw no one there to meet him and walked to Chicago House. When he arrived

Although epigraphers and artists generally wear pith helmets or hats while working in the sun, one of the staff of Chicago House during Hughes's directorship was so concerned about the dangerous effects of solar radiation that he always wore a hat whenever he stepped out-of-doors, even if only briefly. Among the Egyptologists he was called "the Hat." One day, while Hughes was perched high on a ladder at the temple of Medinet Habu (Hughes often spoke of epigraphers' getting "notched feet" like some toy circus figures he used to play with as a boy), intent on his collating, he rather absent-mindedly asked Selim, the ladder-man who stood below him, in Arabic, "Where is 'the Hat'?" The gentle Selim innocently replied, "Oh director, on top of your head."

Hughes developed an ulcer, which fortunately was cured by surgery in Chicago; it required a diet of bland foods, for which he acquired a taste. Understandably, he has not had much liking for fancy cookery. On numerous occasions in the Chicago House dining room he would inveigh against the innocuous artichoke and avocado. Not even the therapeutic qualities of the artichoke, especially for those who had suffered liver ailments, could convince him that it was fit for consumption. For him that vegetable was simply too much of a nuisance to eat.

In 1961/62 he took on the added duties of acting field director of the Oriental Institute Excavations in the Sudan. On January 1, 1964, he stepped down as field director of the Epigraphic Survey and returned to Chicago, thinking he would be able to devote his time and energy to teaching and research. But his colleagues had other plans for him. Without a single dissenting vote, he was soon selected as the seventh director of the Oriental Institute, a position he held for four years, from 1968 to 1972. He served the Institute so faithfully and so successfully that the central administration of the University continued to support the Institute when other parts of the University were suffering financial retrenchment. No ranting, no posturing, just a quiet sincerity, which was persuasive. He is extremely modest. Shortly before the end of his tenure as director he and his wife were dinner guests of some wealthy members of the Institute. The subject of finance must have come up during the evening at some time because these members made a very generous donation to the Institute and stated that this was being done because of their admiration for George Hughes. But he, in his quiet, unassertive way, could never fully believe that it was really because of him that this money had been given.

In 1972, having handed over the directorship to his successor, he was again able to devote all his energy to teaching and research. In 1975 he formally retired from active teaching, but he has remained a source of aid and encouragement to colleagues, students, and his many friends. It was only after his retirement from the University of Chicago that he was able, for the first time, to make use of his other gift, noted by his peers at McCormick Theological Seminary so many years earlier, that of preaching. He stepped in as acting pastor of the church he had been attending for years.

His temperament is reflected in the ancient Egyptian aphorisms he once chose to quote in a convocation address to a University of Chicago graduating class:

"Do not be arrogant because of your knowledge."

"Take counsel with the ignorant as well as with the learned."

"If you are one to whom petition is made, be kind when you listen to the petitioner. . ... A petitioner likes attention to his words better than the accomplishment of that for which he came."

These reflect closely the principles by which he has led his own life. He remains so skilled in his main love, Demotic, that his fellow Demoticists the world over look to him for help with new and puzzling documents, and he remains a warm, generous human being, the "quiet man" who has found "the sweet well for a man thirsting in the desert" (ANET, p. 379).

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

No comments:

Post a Comment